Finishing a 100km run depends less on grit and more on proactive metabolic management to prevent systemic failure.

- The infamous “wall” is a predictable glycogen failure; it can be calculated and managed with a timed fueling strategy.

- Hydration is a balance, not a race to drink more. Over-drinking without electrolytes is a critical, and common, mistake.

Recommendation: Shift your focus from simply ‘eating and drinking’ to managing your body’s fuel, hydration, and recovery systems with a personalized, data-driven plan.

The image of an ultrarunner hitting “the wall” around mile 20 is a cliché for a reason. For many attempting their first 100km, the race becomes a battle against a progressive, seemingly inevitable breakdown. The common advice—carb-load, drink plenty of water, and eat some gels—is often too simplistic to prevent this crash. This advice treats the body like a simple car engine, assuming more fuel is always the answer. However, it fails to account for the complex metabolic systems at play during extreme endurance events.

The reality is that a successful 100km run is a masterclass in metabolic management. It’s about understanding that your body is not a single engine but a network of interconnected systems: your glycogen fuel tank, your hydration and electrolyte balance, your digestive tract’s tolerance, and even your neurological state. Each system has a breaking point. The crash doesn’t happen because one system fails, but because their failures cascade into a total systemic shutdown. This is the difference between finishing strong and a DNF (Did Not Finish).

But what if you could predict and prevent this shutdown? What if, instead of reacting to feelings of fatigue and nausea, you could proactively manage these systems to keep them in an operational state? This guide moves beyond the platitudes. We will not just tell you *what* to eat, but explain the metabolic science behind *why* and *when* to fuel. We will reframe your race strategy from a guessing game into a calculated plan to prevent metabolic failure before the first warning sign even appears.

This article provides a complete framework for managing your body’s critical systems during a 100km event. We’ll explore the science of glycogen depletion, the nuances of ultra-digestible foods, the fatal risks of improper hydration, and the often-overlooked role of sleep and altitude in your metabolic readiness. By the end, you will have a clear, scientific approach to fueling that empowers you to run with intelligence, not just endurance.

Summary: A Scientific Approach to Ultra-Marathon Fueling

- Why Your Glycogen Stores Deplete at Mile 20 and How to Stop It?

- How to Tape Your Feet to Survive 24 Hours of Running?

- Gels or Real Food: Which Is Better for Digestibility During Ultras?

- The Hydration Mistake That Can Kill You: Drinking Too Much Water

- Sleep Loading: How to Bank Sleep Before a Multi-Day Event?

- Why You Wake Up Tired Even After 8 Hours of Sleep?

- Why Fit Athletes Are Just as Likely to Get Altitude Sickness?

- How to Recognize Avalanche Terrain Before You Ski It?

Why Your Glycogen Stores Deplete at Mile 20 and How to Stop It?

The dreaded “wall” that runners hit around mile 20 (or 32km) is not a psychological failure; it’s a predictable metabolic event. It is the moment your body exhausts its most readily available fuel source: glycogen. Your muscles store approximately 500g of carbohydrates as glycogen, with the liver holding another 80g. At a moderate to high intensity, these stores can be depleted in as little as 90-120 minutes. Once this happens, your body is forced to rely on the slower process of converting fat to energy, leading to a dramatic drop in pace and a feeling of profound fatigue. This is not just “getting tired”; it is entering a state of glycogen debt.

Preventing this metabolic crisis requires a shift from reactive eating to a proactive fueling schedule. The goal is to start replenishing carbohydrates long before your tank runs dry. Scientific models have demonstrated this with remarkable accuracy. The key is to understand your personal burn rate and begin fueling early, often within the first 20-30 minutes of the run, to spare your stored glycogen for as long as possible. A typical target for ultra-endurance athletes is to consume 60-90g of carbohydrates per hour.

Scientific Insight: The Rapoport Glycogen Depletion Model

To illustrate this predictability, a mathematical model developed at Harvard by Benjamin Rapoport analyzed how runners experience glycogen failure. The model factored in variables like muscle mass, running intensity (80-95% VO2max), and glycogen density. It consistently predicted a “wall” or point of glycogen failure around mile 21, confirming that this phenomenon is a matter of physiological mathematics, not a lack of willpower. This underscores the necessity of a calculated fueling plan to outsmart your body’s natural limits.

Understanding your personal needs is the first step toward building a robust fueling system. You must move from generic advice to a data-driven strategy. The following framework provides a method to estimate your individual needs and build a plan to avoid glycogen debt entirely.

Your Action Plan: Calculate Your Personal Burn Rate

- Determine Baseline Storage: Start with the baseline understanding that your body stores roughly 500g of carbohydrates in muscles and 80g in the liver. This is your primary fuel tank.

- Calculate Intensity Zone: Identify your target race pace heart rate. For ultra-marathons, this is often in the 65-75% max heart rate zone, which optimizes fat burning but still heavily relies on carbohydrates.

- Estimate Depletion Rate: Understand that a faster pace (closer to marathon effort) can deplete stores in 45-60 minutes, while a steady ultra pace might extend this to 90-120 minutes. This initial 2-hour window is your most critical fueling period.

- Plan Hourly Intake: Based on your intensity and gut tolerance, create a plan to consume 60-90g of carbohydrates per hour. This is non-negotiable for preventing the crash.

- Implement Early Fueling: Your plan must include starting your fuel intake within 20-30 minutes of starting the race. Waiting until you feel a dip in energy is already too late.

How to Tape Your Feet to Survive 24 Hours of Running?

While metabolic fueling is critical, a 100km race can be derailed by something far more mundane: mechanical failure. Blisters, chafing, and hot spots are not minor annoyances; they are race-ending injuries. When your feet fail, your form breaks down, increasing metabolic cost and stress on your entire system. The pain and inflammation can even contribute to systemic fatigue, making it harder to digest food and think clearly. Therefore, viewing foot care as a core component of your overall race management strategy is essential.

Taping your feet is a proactive measure to prevent these friction-based injuries before they begin. The goal is to create a second skin over vulnerable areas, reducing the shear forces that cause blisters. However, a one-size-fits-all taping job is ineffective. Every runner’s foot shape, gait, and shoe interaction is unique. The most effective approach is a personalized one, developed through rigorous testing during your training block. You must become an expert on your own feet.

The process involves identifying your personal “hot spots”—areas prone to friction—and systematically testing different types of tape (such as Kinesio tape or rigid zinc oxide tape) and application techniques. What works for one runner may be a disaster for another. This self-discovery process, mapping your feet’s unique needs, is just as important as testing your nutrition. It transforms taping from a hopeful guess into a reliable part of your race-day system.

Gels or Real Food: Which Is Better for Digestibility During Ultras?

The “gels versus real food” debate is central to ultra-marathon nutrition. There is no single correct answer; the optimal choice depends on intensity, duration, and individual gut tolerance. From a metabolic standpoint, the choice represents a trade-off between speed of absorption and potential for gastrointestinal (GI) distress. Gels are essentially pre-digested simple sugars, providing a rapid influx of glucose. This is highly efficient at high intensity but can lead to sugar spikes, crashes, and, for many, significant stomach issues over the course of a 100km race.

Real foods—like boiled potatoes, rice balls, or sandwiches—offer a more complex mix of carbohydrates, sometimes with fats and proteins. This provides more sustained energy and can prevent the “flavor fatigue” that comes from consuming sweet gels for hours. However, they require more digestive effort. As you run, blood is diverted from your stomach to your working muscles, compromising digestive capacity. What is easily digestible at the start of a race may become impossible to stomach at kilometer 80.

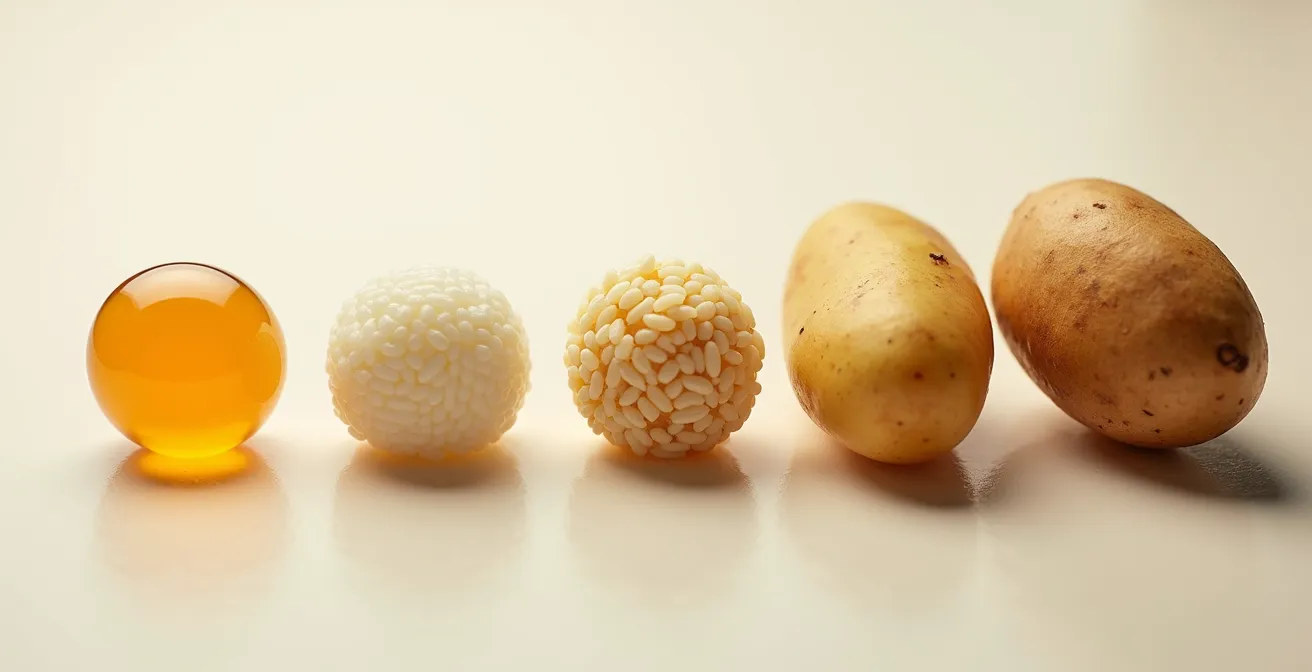

This image illustrates the spectrum of digestibility, from simple sugars to more complex, solid foods.

As you can see, the key is not to choose one over the other but to build a flexible fueling system. Many elite athletes use a hybrid approach. For example, record-breaking ultrarunner Damian Hall uses gels for shorter, faster races but transitions to real foods like salted potatoes and even French fries for longer events like UTMB, where pace is slower and the need for salt and caloric density is higher. His strategy is to listen to his body’s needs for salt versus sugar after many hours on the trail.

Ultimately, your gut is a trainable organ. The ability to process 60-90g of carbs per hour without distress is a trained adaptation. A gradual “gut training” protocol, starting with lower carb intakes during long runs weeks before the race and slowly increasing the amount and complexity, is crucial for building a resilient digestive system.

The Hydration Mistake That Can Kill You: Drinking Too Much Water

The advice to “drink plenty of water” is one of the most pervasive and dangerous platitudes in endurance sports. While dehydration is a performance-killer, a far more acute and potentially fatal risk in a 100km race is over-hydration, leading to a condition called exercise-associated hyponatremia. This occurs when an athlete drinks excessive amounts of plain water, diluting the sodium levels in their blood to a dangerously low point. The symptoms can mimic dehydration—nausea, dizziness, confusion—but the consequences, including cerebral edema (brain swelling), can be lethal.

The risk is not theoretical. A landmark study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 13% of Boston Marathon runners developed hyponatremia, with some reaching critical levels. In a longer event like a 100km run, where duration and fluid consumption are far greater, the risk is even more pronounced. The key to avoiding this is to reframe your goal from “hydration” to achieving hydration balance: replacing not just the fluid you lose through sweat, but also the critical electrolytes, primarily sodium.

This means your hydration strategy must be personalized. Factors like heat, humidity, and individual sweat rate dramatically influence your needs. Drinking to a pre-set schedule or simply drinking when thirsty can be misleading. Thirst is often a delayed indicator, and in long events, the mechanism can become unreliable. The only way to create a reliable plan is to understand your personal sweat and sodium loss. You can perform a simple sweat rate test during training to estimate your hourly fluid needs, and pay attention to signs of high sodium loss, such as white, salty residue on your dark clothing after a run.

Your plan should involve consuming electrolyte drinks or salt tablets alongside water, with the goal of matching your intake to your estimated losses. This transforms drinking from a guessing game into a calculated component of your metabolic management system.

Sleep Loading: How to Bank Sleep Before a Multi-Day Event?

Your metabolic engine is only as effective as the recovery that supports it. Sleep is not a passive activity; it is a critical period of hormonal regulation and tissue repair that directly impacts your ability to store and utilize energy on race day. Chronic sleep restriction in the weeks leading up to an ultra can impair glycogen synthesis, increase levels of the stress hormone cortisol, and diminish cognitive function. In short, a sleep-deprived body is a metabolically inefficient one.

This is where the concept of “sleep banking” or “sleep loading” comes in. Research has shown that you can “bank” sleep in the week to ten days before a major event to offset the inevitable sleep deprivation during the race itself. The goal is to build up a sleep reserve, ensuring your body starts the race in an optimally recovered and metabolically primed state.

This image captures the essence of deep, restorative sleep, the foundation of athletic recovery and energy storage.

A typical sleep banking protocol involves adding an extra 60 to 90 minutes of sleep per night for about a week, starting around 10 days before your race. It is important to then return to a normal sleep schedule for the final 2-3 nights before the event to avoid feeling groggy on race morning. This strategy is not about cramming sleep in at the last minute; it is a structured approach to maximizing your physiological readiness. It’s also supported by a pre-sleep routine that includes avoiding caffeine and alcohol, consuming complex carbohydrates to aid tryptophan conversion, and creating a cool, dark sleeping environment.

Why You Wake Up Tired Even After 8 Hours of Sleep?

For an ultrarunner in the final weeks of a training block, getting 8 hours of sleep but still waking up exhausted is a frustrating and common experience. This isn’t a paradox; it’s a sign that your sleep quality, not just quantity, is compromised. The culprit is often elevated cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. A heavy training load, combined with the psychological stress of an impending race, can create a state of chronic physiological arousal. This “fight or flight” state can persist even during sleep, preventing you from reaching the deep, restorative stages of sleep where true recovery happens.

Essentially, your body is overtrained and under-recovered. High cortisol levels at night disrupt your natural sleep architecture, leading to fragmented sleep and a feeling of being unrested upon waking. This directly impacts your race readiness. Impaired sleep quality means impaired glycogen storage, slower muscle repair, and a blunted immune system. You may be logging the hours in bed, but your body is not performing the metabolic recovery it needs.

This phenomenon is well-documented by athletes and coaches. For instance, Black Iron Nutrition coach Chelsea Myntti detailed her recovery from the Mogollon Monster 100. She found that the immense fatigue loop created during the taper and post-race period was driven by this overtraining-sleep-fuel cycle. Her experience highlighted that forcing sleep without addressing the underlying nutritional and hormonal imbalances was ineffective. The solution lies in actively down-regulating your system during the taper period by reducing training intensity, managing stress, and focusing on nutrition to lower cortisol. Monitoring your morning heart rate variability (HRV) can be a powerful tool to objectively measure your recovery status and sleep quality.

Why Fit Athletes Are Just as Likely to Get Altitude Sickness?

It’s a common misconception that superior physical fitness provides immunity to altitude sickness. In reality, acute mountain sickness (AMS) is a physiological response to a lower partial pressure of oxygen, and it affects individuals regardless of their VO2max. For the ultrarunner, altitude is a profound metabolic stressor that fundamentally changes the rules of fueling. Being a fit athlete doesn’t change the fact that your body has to work harder to deliver oxygen to muscles, and this has direct consequences for your energy consumption.

The most significant metabolic shift at altitude is an increased reliance on carbohydrates as a fuel source. In a low-oxygen environment, your body’s ability to metabolize fat for energy is less efficient, forcing it to burn through your limited glycogen stores at an accelerated rate. Failing to adjust your fueling strategy for this change is a primary reason why even elite athletes can falter in mountain races. Your sea-level nutrition plan will be inadequate.

To quantify this, sports nutrition research indicates a 15-20% increase in carbohydrate intake is needed at altitude just to maintain normal function, let alone race a 100km distance. Furthermore, the dry air and increased respiratory rate at altitude accelerate dehydration. This means your fluid and electrolyte needs are also amplified. Your fueling plan must be adjusted upwards across the board: more carbs, more fluids, and more electrolytes. Additionally, starting to increase iron-rich foods in your diet several weeks before the race can help support red blood cell production, a key long-term adaptation to altitude.

Key Takeaways

- Metabolic failure (“the wall”) is a predictable glycogen event, not a random collapse. It can be prevented with a timed, personalized fueling plan.

- Hydration is a game of balance, not volume. Over-drinking plain water is a serious risk; sodium and electrolyte replacement is non-negotiable.

- Your gut is a trainable organ. Practice your race-day nutrition strategy for weeks to adapt your digestive system to high carbohydrate intake during exercise.

How to Recognize Avalanche Terrain Before You Ski It?

In the context of an ultra-marathon, the most dangerous “avalanche” is not made of snow, but of a sudden, catastrophic metabolic crash. Like a real avalanche, a full-blown “bonk” or bout of hyponatremia doesn’t appear out of nowhere. There are subtle warning signs and a predictable “terrain” of risk. Learning to “recognize the terrain” means developing a deep internal awareness and knowing how to spot the red flags of impending metabolic failure long before the collapse becomes inevitable.

Listening to your body is more than a vague mantra; it’s an active process of self-monitoring. Experienced ultrarunners are constantly running a mental checklist, assessing their energy levels, stomach comfort, and even their thought patterns. A sudden shift to negative thinking or unwarranted irritability is often one of the first neurological signs that blood sugar is dropping. Ignoring these early signals is like skiing into an unstable snowpack; you are willingly entering a danger zone.

This proactive self-awareness can be systemized. One effective strategy is the “Mental Aid Station,” a checklist you run through every 30-60 minutes. As documented by runners, this involves asking simple questions: “On a scale of 1-10, what is my energy?”, “How is my stomach?”, “What are my thoughts like?”. One athlete credits this method for achieving their first sub-3-hour marathon, having recognized early warning signs of irritability and sugar cravings at mile 18. By immediately taking a gel and a short walking break, they corrected their trajectory and avoided the “avalanche.” This demonstrates that the crash is preventable if you know what to look for. The following are five key red flags that signal you are entering the metabolic danger zone.

- Red Flag 1: Unwarranted irritability or a sudden shift to negative thoughts.

- Red Flag 2: Excessive yawning or feelings of drowsiness despite being well-rested.

- Red Flag 3: Intense and urgent cravings for sugar.

- Red Flag 4: A slight feeling of nausea or a queasy stomach.

- Red Flag 5: A loss of coordination, such as tripping, stumbling, or general clumsiness.

By shifting your mindset from simply enduring to actively managing your body’s systems, you transform the daunting challenge of a 100km race into a solvable equation. To build a truly resilient strategy, it is essential to revisit and master the foundational principles of how your body uses fuel.